Ask Our Experts

What you need to know about Monkeypox

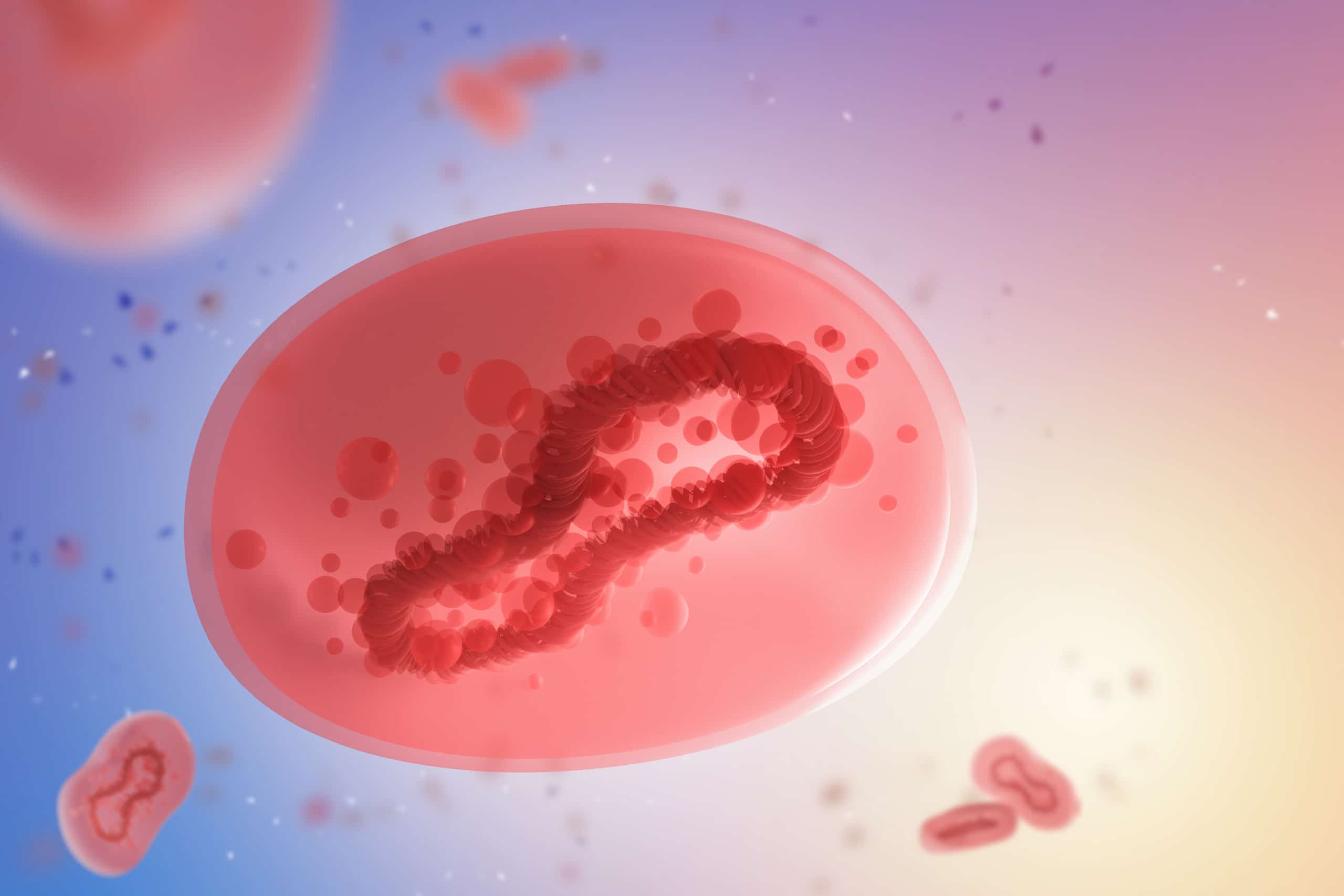

On the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, a new viral concern has emerged – monkeypox. Learn more about the origins of this disease, how it’s spread, and what you can do to keep you and your loved ones safe.

What is monkeypox?

- Monkeypox is a rare disease caused by the monkeypox virus, a member of the same family of viruses that causes smallpox. Monkeypox is much less severe than smallpox.

- Monkeypox was discovered in 1958 when outbreaks occurred in captive monkeys – thus the name. The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- The reservoir host of this zoonotic disease (an infectious disease that is transmitted between species from animals to humans) is unknown, although rodents are suspected to play a role in the endemic setting.*

- Chances of infection in the general population are low, as close physical contact is typically required for transmission.

*Endemic refers to the constant presence and/or usual prevalence of a disease or infectious agent in a population within a geographic area

How is the current outbreak different and why did it make headlines?

- The current global outbreak marks the first time chains of transmission are being reported without links to Central and Western Africa, suggesting person-to-person spread is now prevalent outside the African continent.

- It has been rare for cases to occur outside of Africa. Prior to the current global outbreak nearly all monkeypox cases in people outside of Africa were linked to international travel to countries where the disease is endemic or through imported animals. As stated by the World Health Organization “even one case of monkeypox in a non-endemic country is considered an outbreak.”

Should we be worried?

Individual level: Most people should be aware and informed, but not worried. The chance of exposure for the general public is fairly low. Most cases are mild, sometimes resembling chickenpox, and clear up on their own within a few weeks. Although the disease can be quite serious, particularly for those at higher risk of severe illness,* no deaths due to monkeypox have been reported outside of Africa as of June 22nd. One death was reported in Nigeria in 2022. Of note, the landscape is changing quickly, and like with any virus, monitoring for surges and potential changes in virulence is key.

*People with weakened immune systems, children under 8 years of age, people with a history of eczema, and people who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Global level: The monkeypox outbreak is concerning at the global level. The current outbreak is a significant deviation from the normal endemic state, and unknowns remain:

- The extent of the outbreak is not yet fully understood.

- The scientific community is still evaluating if any concerning changes have occurred in the monkeypox virus.

- It is too early to know if the virus will jump to another animal population causing endemics (constant persistence and spread) in new regions of the world.

Overall, the current outbreak shows that even endemic disease trends can change and flare up, particularly in an increasingly connected world. Constant public health planning and preparedness are needed to effectively respond to the rapidly changing infectious disease landscape across the world.

How does monkeypox spread?

- Those who have visible symptoms are considered infectious. The CDC states that people who do not have symptoms cannot transmit the virus to others.

- Monkeypox can spread when someone is in close contact with an infected person or animal, or with material contaminated with the virus (such as bedding and clothing).

- The virus can enter the body through broken skin, the respiratory tract or through the eyes, nose, or mouth. It has not previously been described as a sexually transmitted infection, but it can be passed on by close contact and exposure to infected monkeypox lesions. New guidance is advising anyone with the virus to abstain from sex while they have symptoms.

- Potential airborne transmission of monkeypox is being investigated. It’s possible that prolonged exposure and close proximity to respiratory droplets can lead to infection.1-3

Who and how many people have been affected?

- As of June 28th, ~4,770 cases have been reported in nearly 50 countries, since the first cases of this outbreak outside of Africa were identified in early May. Though cases from the outbreak have been identified throughout the world, over 85% of reported cases have been in Europe. The CDC has confirmed a total of over 300 cases (~6.5% of global outbreak cases) of monkeypox across 27 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Cases are likely much higher than reported, since testing has not been widely used thus far in the U.S. outbreak.

- Based on demographic information from over 460 cases from mid-June, 99% of cases were in men under 65, most of whom self-identify as men who have sex with other men (MSM). Numbers are expected to fluctuate as more data emerges in the coming months. Though a large portion of the affected population consists of MSM, it is important to note that anyone is at risk of contracting monkeypox.

What are the signs and symptoms of monkeypox?

- The incubation period (the time from the start of the infection to appearance of symptoms) for monkeypox is usually 7−14 days but can range from 5−21 days.

- Symptoms may include fever, headache, lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin), back and muscle aches, and fatigue. Lymphadenopathy is a distinctive feature of monkeypox compared to other diseases that may initially appear similar (chickenpox, measles, smallpox).

- Patients typically develop a rash that can appear on the face, mouth, hands, feet, chest, genitals, or anus.

- The extent to which asymptomatic infection may occur is unknown.

Are vaccines available?

Vaccines are available, but there may be short-term supply constraints in certain areas based on vaccine distribution and demand. As of June 28th, the CDC generally recommends vaccination only to (1) healthcare professionals whose occupations put them at risk of exposure to monkeypox or (2) individuals who were recently exposed to the virus. However, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recently announced an enhanced strategy to vaccinate at-risk individuals by expanding eligibility from only those with confirmed exposures to those who may have been exposed: certain areas had already begun to do this, including New York City.

The two vaccination options are ACAM2000 and JYNNEOSTM. ACAM2000 has been shown to be 85% effective at protecting people against monkeypox before exposure and JYNNEOS has been shown to provide a slightly higher level of disease prevention compared to ACAM2000. Both vaccines are considered safe and effective, but ACAM2000 can have serious side effects – such as heart problems, swelling of the brain or spinal cord, skin disease, and others – particularly for individuals with certain risk factors (e.g., high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, high blood sugar, family history of heart disease, heart or blood vessel problems, skin problems, weakened immune systems, and others). JYNNEOS carries a lower risk of side effects.

In addition to vaccinating before exposure, it may be beneficial to vaccinate after exposure to make symptoms less severe. An approach called ring vaccination consists of vaccinating a “ring” of people exposed to an infected person rather than the entire population. Ring vaccination relies on contact tracing and has been successful in containing smallpox and Ebola outbreaks.

Are treatments available?

Although there are currently no treatments specifically for monkeypox, there are treatments for smallpox that can be used against monkeypox. If you are diagnosed with monkeypox, talk to your doctor about whether any of these treatments is right for you: Tecovirimat (TPOXX), Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV), Cidofovir, Brincidofovir.

Can we contain the outbreak?

Monkeypox and COVID-19 have notable differences. Monkeypox spreads much slower than COVID-19 with cases commonly reporting direct physical contact. Monkeypox also manifests with visible rashes/lesions, making it potentially easier to identify cases. Monkeypox is not believed to spread asymptomatically, potentially making containment much more achievable than with COVID-19. As a result, mitigation techniques like isolation, case management, contact tracing, symptom monitoring, testing, targeted vaccination, and public awareness can be effective at preventing monkeypox transmission. It is imperative that the outbreak is contained to prevent monkeypox from jumping to other animal populations and becoming endemic in more areas of the world.

Additional details below:

- Isolation: Any person with suspected or confirmed monkeypox should isolate away from people and animals until their lesions have crusted and the scabs have fallen off. A person with monkeypox remains infectious while they have symptoms, normally for 2 to 4 weeks.

- Quarantine: As soon as a suspected case is identified, contact tracing should be initiated. Contacts should be monitored daily for the onset of symptoms for a period of 21 days. Asymptomatic contacts can continue daily activities such as work and school. Quarantine is not recommended.

References

- Verreault, D., Killeen, S. Z., Redmann, R. K. & Roy, C. J. Susceptibility of monkeypox virus aerosol suspensions in a rotating chamber. J Virol Methods 187, 333-337, doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.10.009 (2013).

- Milton, D. What was the primary mode of smallpox transmission? Implications for biodefense. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00150 (2012).

- Yinka-Ogunleye, A. et al. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017-18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis19, 872-879, doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30294-4 (2019).